The history of LaGrange’s Confederate monument throughout the past 100-plus years

Published 8:00 pm Friday, June 12, 2020

- Pictured is the Confederate statute in LaGrange on New Franklin Road. — Photo by Dustin Duncan

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Over the past week, a confederate monument on the edge of downtown LaGrange has been the subject of conversation in Troup County.

On Tuesday, LaGrange Mayor Jim Thornton recommended to the LaGrange City Council to place signage at the confederate memorial statue on “The Triangle,” which is a piece of land on New Franklin Road and Franklin Street. Thornton said in an op-ed published in The LaGrange Daily News that he would like the signage to detail the “history of the statue and the ugliness that it represents.”

In April 2019, Gov. Brian Kemp signed Senate Bill 77, which made it difficult for public entities to remove or relocate Confederate monuments.

According to the bill, it is illegal to remove or conceal any monument for the reason of not wanting the public to see it. The bill also says that no monument can be relocated, removed, concealed, obscured or altered in any way. The bill makes exceptions for relocation when it is necessary for construction or expansion projects.

SB 77 also has language making it illegal to deface or abuse the memorial, and says that the party responsible would be accountable for the repairs.

The property where the monument stands currently is city-owned. Thornton said the city does maintain the land and cuts the grass, but he’s not aware of any maintenance specific to the statue.

Pictured is the Confederate statute in LaGrange on New Franklin Road. — Photo by Dustin Duncan

History of the memorial

According to the Troup County Archives, the history of the confederate monument in LaGrange dates back to the late 1800s. Documents say prior to the statue’s creation, a marble tablet hung above the north courthouse door listing the names of confederate soldiers that died from Troup County. Reports from the archives say that the date of its creation is unclear, but it appears a man named W. O. Tuggle was seeking a list of names for it in 1877. Several letters to the newspaper at the time indicated a desire for something more than the plaque, according to the archives.

The first mentions of a memorial statue was suggested in “The LaGrange Reporter” on Feb. 16, 1866, April 5, 1872, and on March 8, 1888.

Documents from the archives say the week before March 14, 1902, bids to create the statue were opened by the Ladies Memorial Association. The Ladies Memorial Association was established in 1866 for the purpose of maintaining the graves of Civil War veterans. By the time the local statue was unveiled in 1902, the ladies had reorganized as a chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy.

The contract to create the monument was awarded to Elledge and Norman of Columbus. The statue was to cost $1,000, and the funds were raised through contributions made by locals whose friends and family members had died during the Civil War.

According to The LaGrange Reporter, on March 14, 1902, the monument was to be “twenty-six feet high, the base and shaft to be of the best Georgia granite which will be surmounted by a Confederate soldier at parade rest, the statue to be six feet in height and carved from Italian marble.”

The archives say the statue was placed on the southeast corner of what was then called Court Square, but now is the corner of East Lafayette and Vernon streets. The statue faced south toward Main Street in October of 1902. The memorial was unveiled during the United Daughters of the Confederacy state convention, which was hosted by the LaGrange chapter.

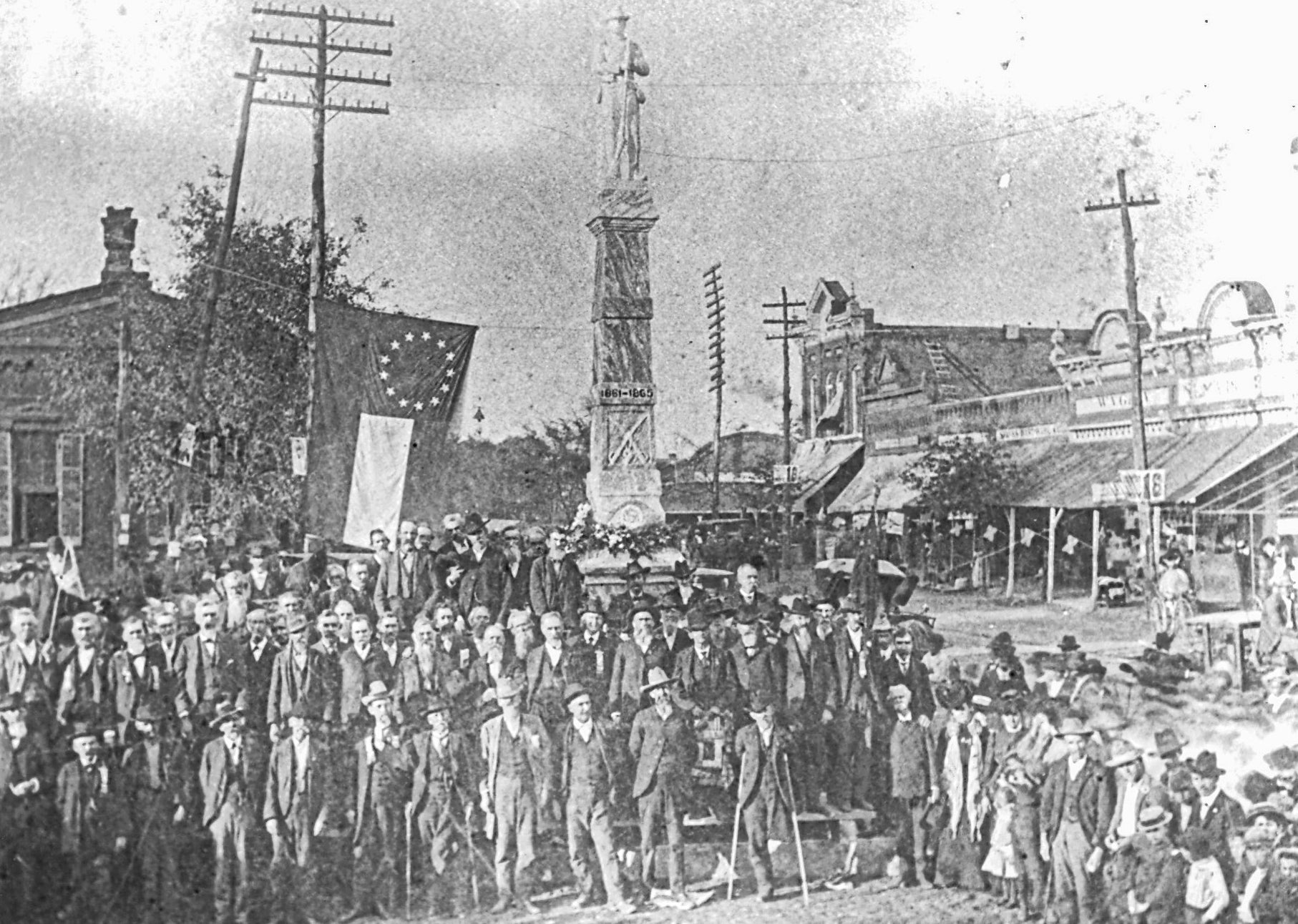

Pictured is the unveiling of the Confederate statue in 1902 by the United Daughters of the Confederacy LaGrange chapter. — Contributed photo

Inscribed on the monument, it says, “Erected by the LaGrange Chapter, United Daughters of the Confederacy to the memory of our Confederate soldiers — those who fought and died, those who fought and lived. In our hearts, they perish not.”

In August 1972, the monument was moved to the yard of the courthouse in Troup County, which is where the Lafayette statue currently stands. The monument faced east and was cleaned that year at the expense of Troup County.

In 1936, the Troup County Courthouse was burned, but the archives says the statue remained on the courthouse lawn after the fire. In 1939, a new courthouse was constructed, which is now the marble building on Ridley Street that services the juvenile court. The archives reports that sometime in the 1940s, the monument was moved to the lawn south of the new courthouse on Ridley and faced west. Documents from the archives say it moved after the new courthouse was built in 1939 and not before the Japanese Submarine was on display on the square in February 1948.

Pictured is the Troup County Courthouse on fire in 1936. In front of the courthouse stands the Confederate monument. — Contributed photo

On March 21, 1962, The LaGrange Daily News reported that the LaGrange Woman’s Club sent a letter to the Troup County Commission saying that “the present location is not suitable and more people, especially tourists would see the monument if it were located on the triangle.”

The commissioners stated they would like to hear from other citizens on the matter, and after receiving what the newspaper reported as “several letters wanting to keep it where it was,”

the commission unanimously voted to let the statue remain on grounds adjacent to the courthouse on April 18, 1962.

In 1976, documents from the archives say a parking lot was planned for south of the juvenile court building, and the statue had to be moved. The Ivy Garden Club and then-LaGrange Mayor Gardner Newman asked the Troup County Board of Commissioners to relocate the statue to the triangle area across from the city cemetery on New Franklin Road. Archived documents say the garden club agreed to take responsibility for landscaping and to maintain the triangle. The club requested that the city and county provide the funds needed to relocate the statue.

According to the archives, the statue has been located on that triangle since 1976 and faces north.

Additional signage

On March 21, 1962, The LaGrange Daily News reported that the LaGrange Woman’s Club sent a letter to the Troup County Commission saying that “the present location is not suitable and more people, especially tourists would see the monument if it were located on the triangle.”

The commissioners stated they would like to hear from other citizens on the matter, and after receiving what the newspaper reported as “several letters wanting to keep it where it was,”

The commission unanimously voted to let the statue remain on grounds adjacent to the courthouse on April 18, 1962.

In 1976, documents from the archives say a parking lot was planned for south of the juvenile court building, and the statue had to be moved. The Ivy Garden Club and then-LaGrange Mayor Gardner Newman asked the Troup County Board of Commissioners to relocate the statue to the triangle area across from the city cemetery on New Franklin Road. Archived documents say the garden club agreed to take responsibility for landscaping and maintaining the triangle. The club requested that the city and county provide the funds needed to relocate the statue.

According to the archives, the statue has been located on that triangle since 1976 and faces north.

Additional

signage

Thornton said the idea of placing signage near a confederate monument isn’t a novel idea, and it has been done in other cities in Georgia. He said he got the idea from the signage installed outside of the courthouse in Decatur. The idea was also furthered when the Lafayette Alliance presented additional signage to be placed near the Lafayette memorial on the town square.

The statue in Decatur was built in 1908 at the DeKalb County Courthouse and was meant to “glorify the ‘lost cause’ of the Confederacy and the Confederate soldiers who fought for it,” according to signage near the statue.

The sign reads the construction of the statue was privately funded by the A. Evans Camp of Confederate Veterans and the Agnes Lee Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy.

“Located in a prominent public space, its presence bolstered white supremacy and faulty history, suggesting that the cause for the Civil War rested on southern (H)onor and (S)tates (R)ights rhetoric — instead of its real catalyst — American slavery,” the sign reads. “This monument and similar ones also were created to intimidate African Americans and limit their full participation in social and political life of their communities. It fostered a culture of segregation by implying that public spaces and public memory belonged to (W)hites. Since (S)tate law prohibited local governments from removing Confederate statues, DeKalb County contextualized this monument in 2019. DeKalb County officials and citizens believe that public history can be of service when it challenges us to broaden our sense of boundaries and includes community discussions of the victories and shortcomings of our shared histories.”

Thornton said he didn’t have a specific proposal for the council Tuesday. Rather, he wanted to have a discussion about the idea of placing signage and if they were open to it. He said the council was amenable to the idea, but they couldn’t approve something they hadn’t seen.

In response to that, the council asked Katie Van Schoor, the city’s marketing and communication manager and Alton West, the city’s community relations director, to look at what other cities have done, consult with local historians and then come back to the council with a proposal.

“My guess is that’s something that’s going to take several months,” Thornton said.

Pictured is a close-up of the Confederate soldier on top of the monument in LaGrange. — Photo by Dustin Duncan

Reaction

Thornton said the conversation with the council was positive and open but several details are left to be determined. However, he said there had been a lot of misinformation spread on social media about what is actually happening.

“You can’t put the cart before the horse on something like that, and that probably was my mistake in a way,” Thornton said. “I just wanted to find out if the council was even open to the possibility of signage.”

He said it seems as if they are open to it, but they are reserving judgment until they see an actual product.

The op-ed published by the newspaper did stir up several comments on social media, which Thornton said was a good thing.

“I regret the tone of some of the comments,” he said. “I wish people were more civil.”

Thornton said he believes many residents want to see the city make progress on race-related issues.

“Sometimes, social media can result in a very harsh, strident, angry tone,” he said. “Social media is great and has a lot of great qualities, but that’s one of the downsides of it.”

However, Thornton said it was important for the community to have a conversation about the statue and race in general.

“I’m not, at all, unhappy with the fact that people are engaging in these conversations and trying to understand other people’s perspectives,” he said. “The most important thing that I wish more people would do is listen and try to understand how other people see, sometimes, the same events and the same context.”